An artist of prodigious talent, recognized at genius and master by his peer and critics, celebrated by the community leaders of the day, LeRoy Foster nevertheless worked and lived to please himself. In 1993, at age 67, he died penniless and near obscurity; and his body of work, called that of the “Black Michelangelo” by Dr. Charles H. Wright, was virtually forgotten. Except for his Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, created for the Detroit Public Library, and a handful of other murals in institutions around the city, Foster’s life’s output of paintings and drawings was held exclusively in private collections. The Detroit Institute of Arts, where he literally danced through the halls and galleries as a teenager, and which included his work in a traveling exhibition in 1968, did not own a single Foster.

In the present retrospective exhibition, “The Soul of LeRoy Foster,” Hannan Center’s Ellen Kayrod Gallery, under the direction of Richard Reeves, seeks to redress what at last is broadly acknowledged as a grievous oversight of one of our greatest artists.

Simply Tree strikes immediately in its eerily twisted leafless form while it communicates strength and a wisdom that comes from long life. It reads monochromatic but up close hints of green and sienna appear in the umber bark. Faintly metallic gold is lightly brushed over a previously dark background granting depth and texture. Monstrous scale is established via the figure in the foreground which is mirrored in a tiny silhouette to the left of the trunk.

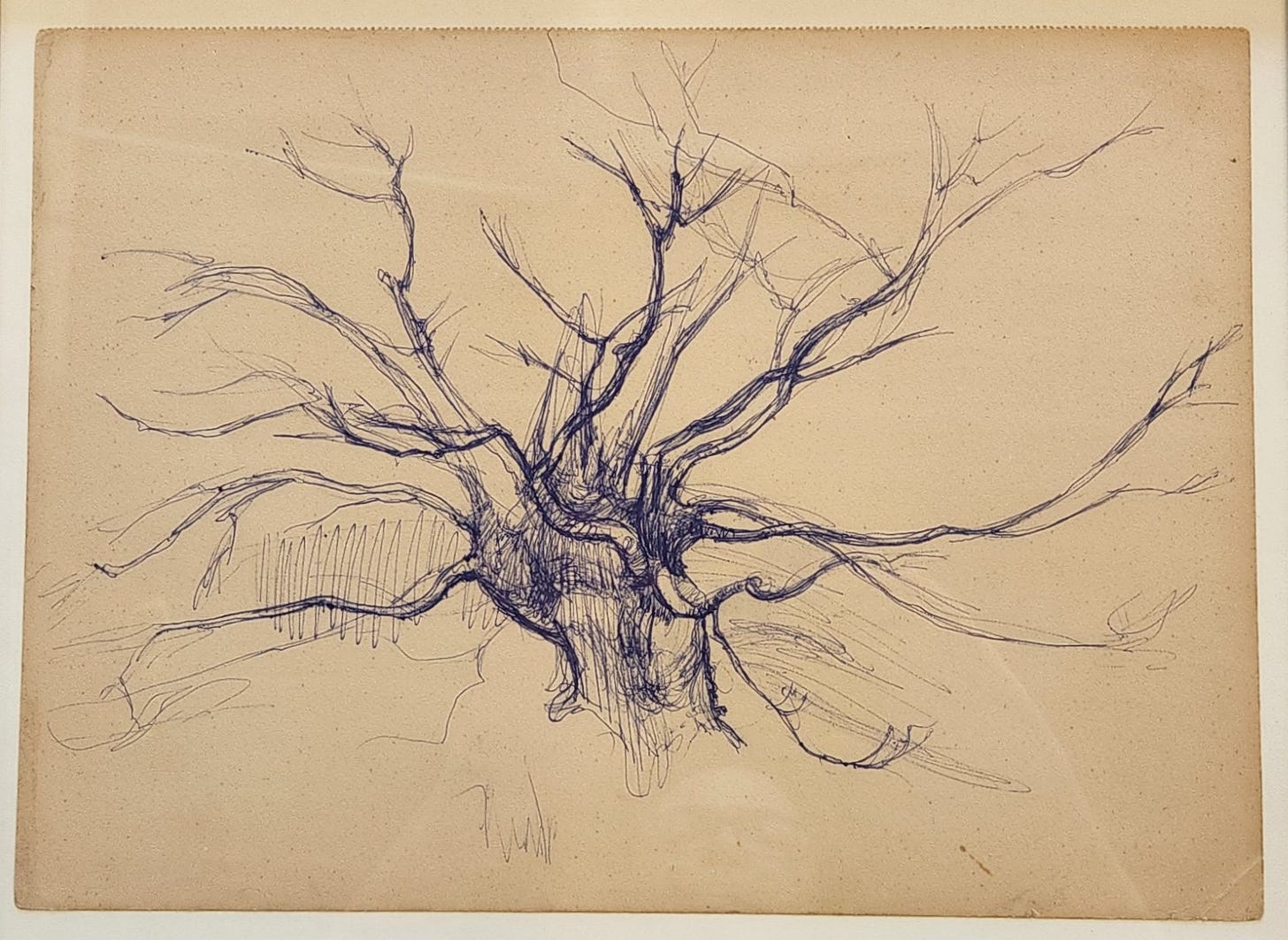

It's a treat to have the sketch for this masterpiece. Drawings afford an intimate look into an artist’s process and reveal foundational skills in use of line, shading and composition. The drawing is heavier and pronounced in the center where the artist is pressing down on the pencil. By the time the branches reach their full breadth, they are mere wisps of graphite—probably lead actually—as the artist lightens his touch. There is freedom in the loose, expressive marks at the edges of this aged sheet of paper.

The latent physical strength is palpable in Mythological Figures. Foreshortening is spectacular in that the left hand and knees come straight out toward the viewer, highlighted in earthy reds. Foster’s admiration for High Renaissance painters is evident yet he communicates his story in an abstracted arrangement with an impressionistic application of the paint. This work not only presents technical excellence, it’s masterfully expressive.

Interestingly his abstract is more carefully rendered than the paintings with a clear subject. While remaining difficult to discern precise objects, this interprets as a still life, perhaps a plate of food on a rumpled tablecloth. He employs the Renaissance’s deep contrast of light and shadow to create drama in an otherwise mundane composition.

LeRoy Foster was very well known while he was actively working, including training in Europe where his first commissions came from collectors in Paris. Somewhere along the line because he is a Black artist, the work receded into history. Like too many others, I had never heard of LeRoy Foster, which sadly substantiates the myth that an artist only reaches lofty heights of recognition posthumously.

After Foster died indigent at Harper Grace Hospital, the American Black Artist, Inc. gallery’s collection of his paintings, valued at $8 million, was donated to The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History.

“He was just LeRoy, and that was beautiful,” Foster’s lifelong friend Charles McGee said, “He was a beautiful human being.”

On view through August 15th at Kayrod Gallery 4750 Woodward, Detroit

*images are mine

direct quote, reference from gallery materials written by Michael Madigan

If you are enjoying this newsletter, please consider supporting it by becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

SHOWS OPEN THIS WEEKEND